III. Indirect exposure therapy

"Cradled too close to the wall. As in, her head kept banging on the walls when she was a toddler."

Recap –

One of the ranch’s helpers befriends two brothers running an auto shop and discloses details about the reintegration program and their upcoming journey across Canada.

The two managers make the ultimate decision to kick Hedy off the program as she’s a liability and hasn’t been able to bond with the horse that was assigned to her. Hedy has a breakdown, being remembered once again that she’s unable to fit in and live a “normal” life.

Companion Playlist —

Chapter III. Indirect exposure therapy

Tad lights a new cigarette with the dying cherry of another one, nodding to an old-timer tune on the radio. He crosses the ranch’s main gates in J.R.'s pickup and parks it at the front, next to a beat-up tank-style bobcat and other lightweight agricultural equipment barely younger than Boggs. He rolls down his hoodie’s sleeve to cover some needle spots in the crook of his elbow and jumps down.

Hedy stands by the bobcat, a flashy lime suitcase and two hockey bags by her side. Her toes kiss each other and she can’t manage to look elsewhere than the gravel.

“J.R. around?”

“I am supposed to meet Mister J.R. and Mister Boggs here at three-thirty, yessir.”

Tad giggles, “Mister J.R. and Mister Boggs, right on. Hedy, right? Going somewhere?”

“They say I’m going back to Marta now. She has to take Road 28 Westbound till Road 16 Northbound for seven miles and–”

“Alright, alright, lemme help you with the bags then.”

Tad grabs the suitcase and a hockey bag, but Hedy holds on to the other one, “No no no, this one is for Mister J.R. and Mister Boggs, not this one, this one stays, it–”

“Alright, alright, my bad. No worries, ain’t stealing it.”

Boggs shows up with J.R. “Hey, kiddo. You early.” And they all look at each other, not sure what to say, whether to smile or not, those manly men suddenly very ill at ease.

“Let’s see that hitch ball then.” J.R. goes behind the truck and kneels to study Ian’s work, Tad next to him.

“Two brothers made it for 350. It’s 2 and 5/16th inches, the pin’s through the lock, right here, chains right there, and the younger brother—guy was a fucking ace by the way—put a breakaway cable, in case all shit goes loose. Decent work, eh?”

“Perfect. Boggs?”

“Beats a gooseneck any day.”

J.R. stands up. Scratches his throat, kicks a few rocks. Avoids looking at Hedy. Shoots a look at Boggs who pretends to be really focused on a pair of birds in the trees over there. Bluejays, maybe? At this time of the year?

And so J.R. finally says, “Packed everything, Hedy?”

Hedy tiptoes to them, dragging her heavy hockey bag behind her and struggling to grab a piece of paper from her shirt’s chest pocket. She reads, as best she can, “I want to give you this and hope it will be a source of help during the trip. I also want to thank you for the opportunity you gave me to work on your ranch with horses. I am sorry I couldn’t make the knot and couldn’t pet Wrench and play with him. I wish you the best in your future endav... edena... endvour--For the future.”

“Well, it’s… Thank you, Hedy.” J.R. spots the three other women in the distance, spying on the scene. Hedy gives them a little anxious goodbye wave, the one kiddos give their parents on the first day of school.

“You’ll be taken care of, Hedy, OK? Someone from social services agreed to meet us in Brandon. They’ll drive you back to Winnipeg.”

“Can I say goodbye to Wrench?”

“Wrench is… Now’s not the best time. He’s with the vet.”

“Is he sick, is it a cold?”

“Just a routine check. He’s fine.”

Enough for Boggs, who stops pretending he’s really into birds and just says, “Well.” He grabs the hockey bag and makes for the office without a word, but J.R. spots him rubbing his nose a little bit.

“Jump in, Hedy.”

Boggs limps in J.R.’s office, drops the heavy hockey bag on the desk and takes a seat in J.R.’s chair. Pecks on some sunflower seeds but they don’t taste as good as they usually do.

There’s the hum of the pickup’s engine now, and he can see it drive away on the long dirt road over there, lifting a little bit of dust behind it, just a small dot in the prairie now.

Eyes back on the hockey bag. Pecks on more seeds. Remembers that time when he was six or seven and he got up early one Christmas morning, up before his parents and seven brothers and sisters in the bunkhouse, and he had so much adrenaline in him he couldn't resist opening the one gift he received. He made sure he could properly fold the newspaper wrapping back on itself afterward, careful not to tear anything too much. It was a carved horse his dad made, with the name “Pepper” written at the bottom, about the size of a pack of cigarettes. Carved nicely enough that the dad could’ve gotten a bit of money out of it. And so baby Boggs played with Pepper in the dark and cold mining shack they lived in, going on adventures up on these bags of flour that became “The Snowy Hills”, across the firewood pile that turned into “The Caribou Forest”, splashing around in soapy water that he renamed “Windy Lake” until he could hear someone waking up. He kissed Pepper and wrapped it like it was ten minutes ago, put it where he found it, and greeted his father who just came into the kitchen. But Baby Boggs got caught and took a beating that morning, and when he told this story he said he still has the imprint of his father’s hand on his bum cheek, but it was all worth it. These ten minutes of adventures with Pepper were the highlight of his childhood, the one time he had a moment to himself as a kiddo.

And so he reaches for Hedy’s hockey bag on the desk and opens it before J.R. comes back.

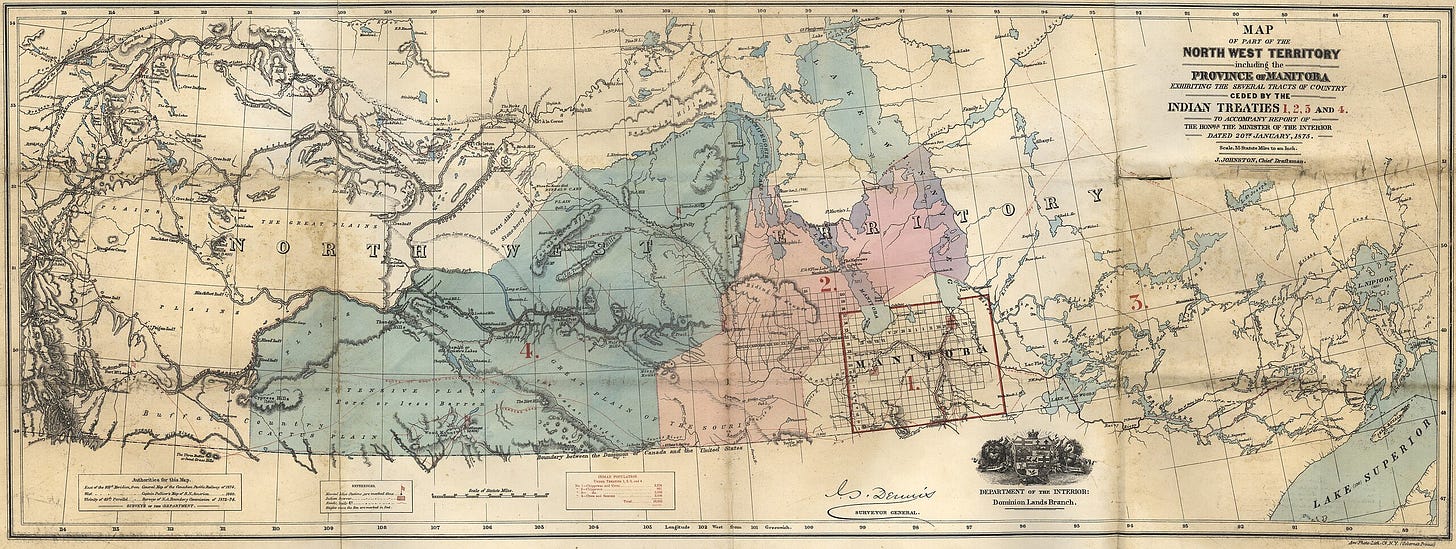

Atlases and topographic maps. Massive ones, actual books. About twenty of them, the very detailed kind. Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia. Different editions of different years, going as far back as 1967. Boggs flips through the “Alberta” one, the 2004 edition. Sticky notes everywhere, almost on every single page. Hand-written inscriptions in the margins too. A yellow streak maps a main route through the detailed maps, across the pages, even across the different provinces’ atlases as Boggs now spreads every book on the desk, shoving everything else on the floor. Red streaks for alternative routes. Green dots for camping sites. Ravine isn’t as stiff in the 2018 edition — mistake. Hospitals and veterinary clinics circled in pink. Bridge appears in 2019 edition — recent, reliable. Printed pictures of what the public campsites look like in the annex section. Hilltop near higher one — protected from north winds.

Bunny ears, bunny ears, playing by a tree. Criss-crossed the tree, trying to catch me... Hedy rehearses her knot with her shoelace, again and again, and she’s so fast and agile now she could win a national contest.

Even J.R., driving, is impressed with how much progress she made. “You like that knot, eh?”

“Keeps the gates closed.”

“Hey, how do you remember all the roads? When you said, you know, what roads that Marta character had to take?”

“I got lost once and didn’t like it, so Marta said I should check maps and understand how space and direction work. She said it was-- she called it “indirect exposure therapy”, yes, that’s what she called it. I spent six years with maps and atlases.”

“Liked it?”

“Tells you where to go. And how. It’s codified, it has rules, yes, a language. It’s reliable. Tells you how to run away or where to hide.”

“That Marta helped you a lot?”

“Never ever said mean and ugly words to me.”

“That’s good. She’ll be–”

His phone rings. “BOGGS”.

“Yup, Boggs, we just passed the–”

“--She mapped it all out, kid, from Manitoba to Alvaret in BC, all of it, she got fucking atlases bigger than the Bible, different years, compared all of them, found alternative routes, campsites, potential problems like high water, muck, cliffs that couldn’t be passed and others we could try, she... Listen, kid, I mapped a route in the Rockies that would’ve taken us three days from point A to B, got that? She mapped something different and it only takes fucking half of it. Piece of art this is, I tell ya, you could sell that darn thing and not work another single day out your life, kid’s got a gift.”

All J.R. can do now is stare at a clueless Hedy who still rehearses her knot, quicker than ever.

“You listenin’? Eh, I’m talking to you, J.R.!”

J.R. hits the brakes and makes a sharp U-turn on the dirt road.

Needle through, thread up, needle through, thread down. A rough embroidery of a horse made of gray threads. Jean works on her craft next to Oneida and Hazel, sitting on makeshift benches behind the ranch, the big open prairie ahead of them where their three respective horses graze. Hazel was paired with Verlaine, a gray mare that she managed to approach and train very early on in the program. Jean was with Nam Nam, a young brown horse who could run and run and never stop, as if he was born with two hearts, and she joked that he probably was the one to plot the escape yesterday, or maybe Munly, who could be sly that way as well. Oneida’s horse. An odd sort of disdain in him, like he’s better than you and you’re just wasting his time. He gave a hard time to Oneida at first, but the two came to an understanding.

Oneida studies Jean’s embroidery, the precision it requires, the way she puts her nose very close to the canvas before taking her distance to see the full thing, her head slightly tilted like a dog unsure what you just said.

“How’s working with needles?”

Jean searches for her words. “Its.. Fine. But, yeah, at first, I thought about it all the time. I was mostly smoking it, fentanyl, but I was injecting some stuff too, sometimes. So I thought about it all the time, like a neuronal connection that won’t shut up. It’s better now and I like the idea of giving a new sense to an object. Find a healthier love for it.”

“When I was on the res’, we had–”

But Hazel interrupts, empty gaze ahead, “Hey, did J.R or Boggs ever tell you what’s the deal with Hedy? Like, what she has?”

Jean continues her embroidery, “Cradled too close to the wall. As in, her head kept banging on the walls when she was a toddler or something. The French say that for someone who’s a-- Well I’m not gonna say “retard” again, but I guess the PC way to say it would be simpleton.”

It gets a giggle out of Oneida. “What did she do to serve eight years in that psychiatric institution, that’s what I want to know. But no, I don’t know. Autism, maybe. They never told me. Maybe they don’t know themselves. But I imagine she was diagnosed with something at some point if she had to go somewhere else than prison. Boggs felt pretty shit about it all. Kicking her out the program and everything.”

Hazel is still in a mental fog. “If she was my kid, if she was my child, I’d probably be OK with their call. It’s for the best, I reckon. Not just for us and the program, but for her. I think, someone like her, it’s... There’s help needed, you know. Day in, day out. From people who know what they’re dealing with. Yeah, if it was my kid, I wouldn’t give a hard time to the boys.”

The three horses raise their heads at the same time, eyes on the main dirt road over there and this pickup driving way faster than usual.

J.R. smashes the brakes when he reaches the front gate and jumps off the truck without even turning the ignition off, headed toward his office. Hedy’s left behind, clueless, so she tiptoes like fog behind him. She spots Wrench in the arena, standing still near the gate, and can discern the two guys over her atlases in the office, all spread out on the desk. She continues forward, as discreet as a barn cat, until she can hear Boggs.

“Five of them of Alberta, and three of B.C., all different years, compared them all.”

“What’s the yellow lines?”

“Main route. Pink dots and circles, here, it’s hospital and vet clinics. On the margins here, she listed the towns less than 50 kilometers away from the main route and what they had. Commodities, gas stations, auto-shops.”

“How the fuck does she know all that?”

Hedy’s in the doorway now, and she spooks them both a little bit when she speaks up. “Indirect exposure therapy she called it, yes. They had maps where I was and the people in gowns and masks they showed me the maps and I studied them eight hours a day at least, studied the lands and the railroads and the boutiques and shops and the topography. They had maps for everything, these atlases here is just a little bit, just what I could carry, there was way more.”

J.R. flicks through them, impressed. “Are these from where you were?”

“Marta said I could keep them, when the men in gowns and masks said I could leave, she gave them to me, said no one looks at them anyway, dust on the shelves she said, said there’s phones now and it’s all vestige she said, I didn’t steal them, it’s not true, I-- No, I didn’t–”

“Easy now, kid, no one’s accusing you.” Boggs winks at her and looks at J.R., all proud like he found a truffle pig for free.

J.R. turns to his uncle, both talking low-voiced. “A map reader?”

“They move cattle over there, multi-day trips. It’s huge.”

“Scouting new areas too, why not?”

“Next year’s program, map it out.”

“Put her on a software, create maps, she’d speak that language.”

“Expansion and stuff. New pastures.”

“Branch out, who knows, a second sanctuary up North, pair her with a GSI technician, some ground samples to develop agricultural lands.”

“Merle would be all over that shit.”

“OK.”

“OK.”

J.R.s fetches his cell from his pocket and exits the office, giving a big tap on Hedy’s shoulder on his way out.

And Hedy looks at an imaginary point on the wall above Boggs and rocks back and forth, not sure what to make of what happened.

“He’s calling Merle. Good work, kiddo.”

She keeps rocking, but now with a little dainty smile on her face.

“Does it mean I can go play with Wrench just for a little bit more?”

Chapter IV

Chevalier’s way with words really pulls you into the Canadian prairies. The mix of rawness and beauty in the book has definitely grabbed my attention, and I can’t wait to dive into the next chapters to see where the story goes!